Lost In Space – Chapman University

2007

Solo Exhibition | Guggenheim Gallery, Chapman University | 2007

Catalog Essay (excerpt)

DRAWING IS A VERB

by Carrie Paterson

Chris Natrop - "Lost in Space"

Guggenheim Gallery, Chapman University

February 5 - March 23, 2007

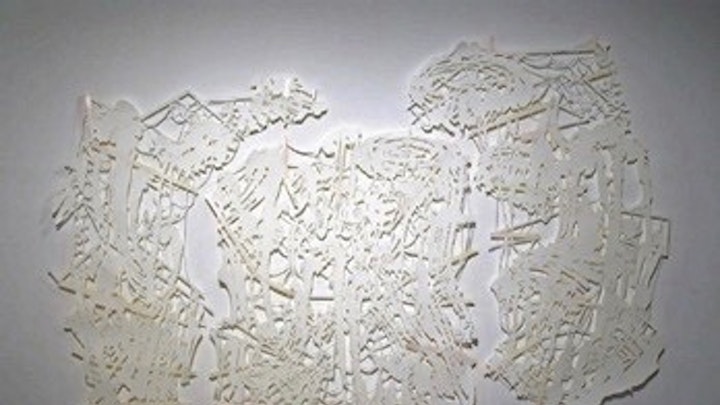

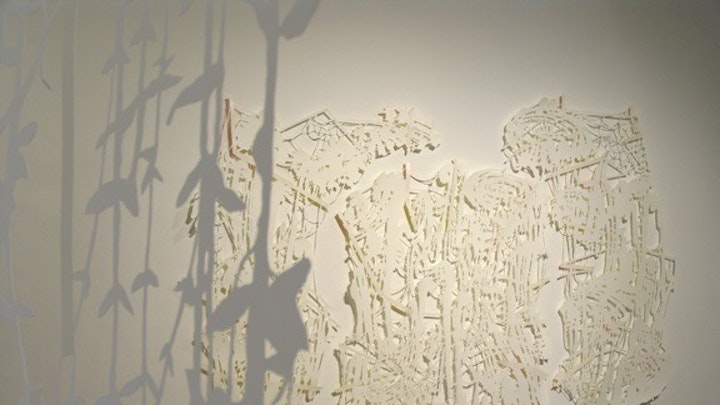

In Natrop's "Lost in Space", the scale and delicacy of each sprawling piece seems as unlikely as it does beautiful. At first glance the cut paper landscapes grace the walls of the gallery like an organic wallpaper, fragile and impossible to repeat. Smaller recognizable images - vines, palms, the girders of an overhead freeway - come to our attention only after this first impression. That Natrop has made all of these intricacies by hand becomes obvious upon closer investigation - there is no architectural CAD machine powering the image, no digital "original" that can spit out copies of itself to populate a world already replete with replications. But what is not so obvious is that Natrop's own towering figure, 6-foot-plus, is intimately recorded in the installation. While not usually remarked upon, this aspect of the work is important to the artist. "My physicality is integrated into the work," says Natrop who says he doesn't really build over his own "wingspan." Because of his size, he says he naturally thinks on a different scale, and when approaching a gallery wall thinks more of "scaling it," rather than simply hanging his work on it, to create a "precarious and uneasy" situation.

When Natrop arrives in a space, whether that be the gallery or a sheet of paper, he starts to explore and discover the negative space. "I see the emptiness as a solid object. I discovered that emptiness is a thing through the actual process of cutting paper." What Natrop endeavors is to reveal the negative space, the invisibility itself that is hidden by the objects with which we surround ourselves. In a turn-about to traditional Western cosmologies which prioritize objects and use them as orientation devices, Natrop finds space to be primary. "Technologies and frequencies in the world connect everything," he says. "All boundaries are permeated." Natrop's papers act as visual corollaries to these unseen bridges which connect all of us. The emergent network is the human condition: there are no distinct objects in space, only relationships.

Natrop's works seem ephemeral - an illusion that he embraces - but are durably constructed so as to be transportable, trans-mutatable. He recombines them in an improvised fashion in each location they live. While the process of creating the works has Natrop "lost in space" on the page, cutting his way toward familiar images and memories of wandering through his his new home (Southern California), this activity is also repeated on the blank white walls of the gallery with Natrop literally projecting his body against the void to attach and arrange his former visions. Like a gardener of air, he cultivates the nothingness of space into something we can see. Here we might find a city peeling off the wall to reveal an Eden in between.

That Natrop's forms often hint of the natural seems fitting as he responds to the lack or marginality of such in the topography of Los Angeles. While not a specific transcription of his surroundings, Natrop's environment is familiar to us, as if we've already seen an accumulation of this space at speed but are slowed here to look at what we already know. The work suggests that we perceive the world through a lens of technology grafted to us by our habits of doing business. The extended act of contemplation and emergency Natrop presents in "Landing Nowhere Else", "White White Mayday in Mustard and Gold", and "Black Black Butterfly Sparkle Bomb" freeze us in that moment of arrival, where the unfamiliar nuances of such strange surroundings hold us temporarily captive.