Of Night and Light and Half Light

2015

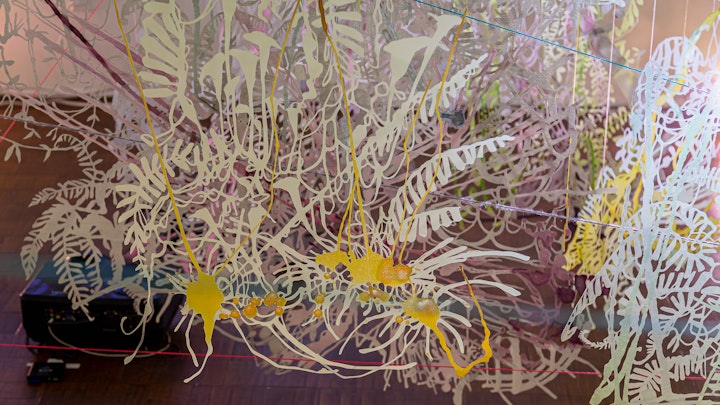

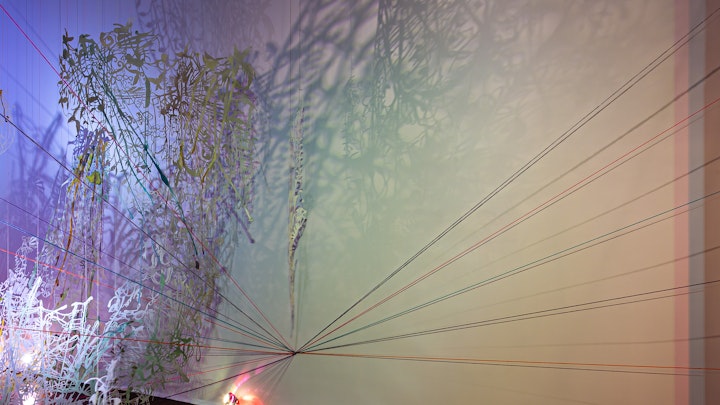

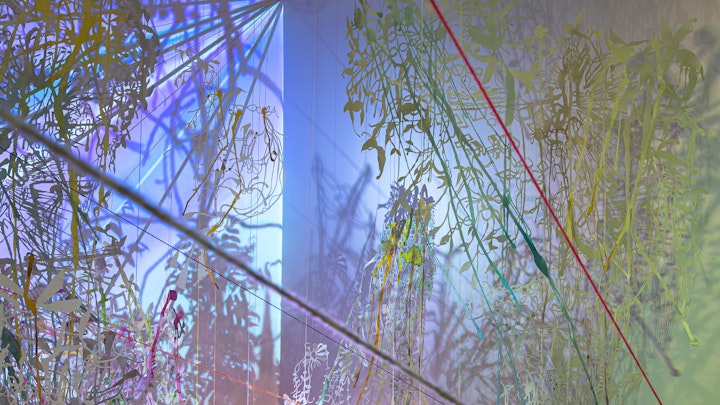

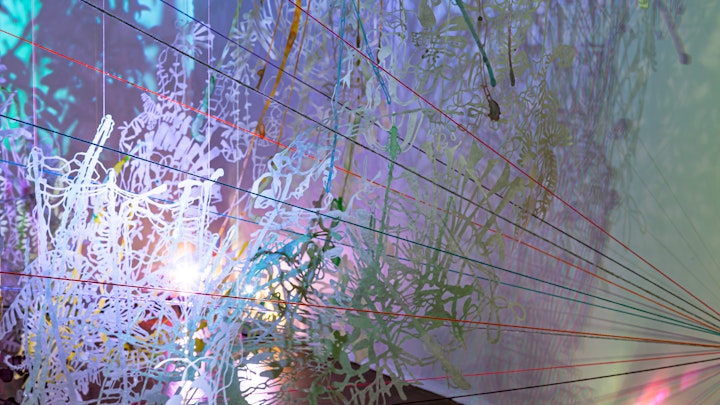

120 x 216 x 120 | watercolor, metallic powder, glitter on hand-cut paper, string, yarn, projected video, lighting | 2015

Craft and Folk Art Museum | Los Angeles

The jungle is a magical one, dense with dangling vines and voluminous blossoms awash in green and gold glitter. The foliage sways in the breeze, casting glimmering shadows that dance on a nearby wall to the chorus of crickets chirping, leaves rustling and crows cawing. Chris Natrop’s hand-cut paper forest at the Craft & Folk Art Museum is part of the exhibition ‘Paperworks,’ which features sculptures, collages and large-scale installations by 15 contemporary artists working in unusual ways with paper. Using a somewhat crude box-cutting knife, Natrop carved a 3-D forest that is backed by video from his own garden. The color-washed paper forms, often with rough or frayed edges, dangle from the ceiling and drape along the floor like an overgrown yard, the organic sounds from his garden bringing the installation to life.

— Deborah Vankin, Los Angeles Times, art critic

Catalog text by Howard N. Fox

Chris Natrop creates artworks in public spaces on a public scale; brass and stainless steel are his preferred and required mediums (for permanence) in these commissions, which dot sites around the United States from Los Angeles International Airport to the shop windows of Harry Winston jewelers in New York and around the world[verify]. But these grand projects derive from Natrop’s primary interest in paper cutting and assembling paper constructions, particularly for site-specific situations.

Natrop does not believe in the inevitability of final form and presentations; tentativeness and serendipity are very much part of his aesthetic practice, and he curries improvisation as his working method. Typically, Natrop – easily six-feet tall – begins one of his wall-mounted sculptures by placing a seven-foot long (or longer) expanse of unrolled Lenox 100 drawing paper on the floor of his studio and pouring, dripping brushing, or spattering colored dyes and acrylic paints onto the surface, as he picks up the edges of the paper sheet to encourage the random flow of the paint over its surface. The result is a dynamic, intensely colored abstract painting, on paper, that is an homage to both gestural abstract expressionism and color-field or stain painting from mid-twentieth century modernism. But Natrop is not content to celebrate the flatness and formal purity that influential art critic Clement Greenberg proposed as an artistic ideal in his lionization of those late modern movements.

Natrop is a bit of an iconoclast and trouble-maker for such ideals. For, draping his long strip of “painted” or stained drawing paper down the studio wall all the way to the floor, he proceeds to cut shapes out of it. Unlike several artists in this Paperworks exhibition who use scalpels and X-ACTO knives, which are prized for their capability to create very precise cuts, Natrop (who reports that he has a neurological disorder that prevents him from making such precision cuts) uses a box-cutting knife – a particularly “primitive” tool whose main use is expressed in its very name – to subtract elements of the composition, ripping into areas of the paper or cutting them away with the crude knife blade, which has the effect of creating a second composition of voids and holes implanted into his painted paper hangings. Often he mounts the resulting painted and cut paper works a couple of inches in front of a wall, creating yet a third compositional layer of cast shadows on the wall of the “white cube” of the gallery space, while sometimes allowing the long, long paper-based painted and sliced objects to cascade onto the floor and to creep up onto the ceiling, or even suspending them in open space as free-floating constructions.

These works, which are hybrids of two- and three- dimensional modes, are visually exciting and a bit unruly. There is a quality of robust visual restlessness and aesthetic muscularity to Natrop’s audacious commandeering of architectural space; he seems to willfully vie for attention with gallery spaces or public settings. Of course, the same may be said of any but the tamest, blandest works of site-specific or public art projects. But Chris Natrop’s work is neither tame nor bland; it cheekily engages its surroundings, stoutly engaging both the viewer and the space they share in the gallery.